General Information about Primaquine

Primaquine is a extremely effective anti-malarial drug that belongs to the group of 8-aminohinolina derivatives. This treatment is taken into account a key part in the battle towards malaria, an epidemic that affects tens of millions of individuals every year. With its distinctive mode of action, primaquine has confirmed to be efficient in treating numerous types of malaria and has saved countless lives.

Primaquine is available in both oral and injectable forms, and its dosage and duration of therapy vary relying on the sort and severity of the malaria infection. The drug is usually well-tolerated, with no serious unwanted effects reported. However, like all treatment, it could trigger some gentle side effects corresponding to nausea, headache, and abdominal pain.

In addition to its anti-malarial properties, primaquine has also proven to produce other helpful effects. It has been discovered to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects, which can help in lowering the severity of the illness and its signs. Moreover, primaquine has a significant influence on lowering the number of malaria relapses, making it an important drug in stopping the recurrence of the illness.

One of probably the most notable properties of primaquine is its high activity in opposition to the primary tissue types of Plasmodium falciparum, essentially the most lethal species of malaria. This is because of the drug's capability to successfully intercalate with the parasite's DNA and disrupt its nucleic acid synthesis. This makes primaquine an essential component in the remedy of extreme cases of malaria brought on by Plasmodium falciparum.

One of the primary mechanisms of primaquine's anti-malarial activity is its ability to intercalate with DNA within the parasites, particularly the plasmodia that causes malaria. This intercalation leads to disruption of the synthesis of nucleic acids, which are important for the parasite's survival and replication. As a outcome, the parasite is unable to breed and cause further harm to the body.

Primaquine is most commonly used within the remedy of the exo-erythrocytic forms of all kinds of malaria. This consists of both the primary tissue stage and the para-erythrocyte stage of the disease. The primary tissue stage refers to the parasite's improvement within the liver, while the para-erythrocyte stage is when the parasites infect pink blood cells. By concentrating on both of these phases, primaquine is in a position to effectively remove the parasites from the physique and prevent the disease from progressing additional.

In abstract, primaquine is a powerful and effective anti-malarial drug with a novel mode of motion. Its ability to intercalate with DNA in the parasites makes it highly active in opposition to all forms of malaria, especially the lethal Plasmodium falciparum. Its role in preventing relapses and lowering the severity of the disease makes it an integral part within the battle against malaria. With ongoing research and improvement, primaquine continues to hold nice potential in eradicating this global health threat.

Available data suggest that persistent or progressive disease will occur in one-third of conservatively managed cases (Clark et al 2006) treatment hyperkalemia discount primaquine online mastercard. Various approaches have been tried in order to achieve this aim, including clinical, chemoprevention and prophylactic surgery. Large clinical trials are currently underway, investigating the potential of such screening programmes in both low- and high-risk populations. Chemoprevention has particularly focused on the use of the oral contraceptive pill, which has been shown to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer in both low- and high-risk populations (Hankinson et al 1992, McLaughlin et al 2007). The timing of surgery is dependent on the individual, their fertility requirements, the potential surgical morbidity and long-term hormonal sequelae. The current advice is that surgery should be considered once a woman reaches 35 years of age. Prophylactic surgery, however, does not completely remove the risk of malignancy since women in some highrisk populations are still at risk of developing primary peritoneal carcinoma (Finch et al 2006). The pathological evidence for the progression of type I tumours arises from studies which have shown the frequent occurrence of a transition or coexistence between malignant and benign areas in mucinous ovarian cancers, and between low-grade serous cancers and areas of borderline change (Malpica et al 2004). Also, borderline serous tumours typically recur as low-grade serous cancers (Crispens et al 2002). Cervical cytology can prevent 75% of cervical cancers by enabling early detection and treatment. Colposcopy is subjective, has significant inter- and intraobserver error, and a sensitivity for high-grade disease of only 50%. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia should be managed as if cancer, as up to 45% of cases will be found to have endometrial cancer at hysterectomy. Ferenczy A, Gelfand M 1989 the biologic significance of cytologic atypia in progestogen-treated endometrial hyperplasia. Fukunaga M, Nomura K, Ishikawa E, Ushigome S 1997 Ovarian atypical endometriosis: its close association with malignant epithelial tumours. Jimbo H, Yoshikawa H, Onda T, Yasugi T, Sakamoto A, Taketani Y 1997 Prevalence of ovarian endometriosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis E 2006 Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sasieni P, Adams J 1999 Effect of screening on cervical cancer mortality in England and Wales: analysis of trends with an age cohort model. Smith-Bindman R, Kerlickoske K, Feldstein V et al 1998 Endovaginal ultrasound to exclude endometrial cancer and other endometrial pathologies. Although the incidence of cervical cancer has decreased in industrialized countries in the past 20 years, it still remains a major problem in the developing world. Carcinoma in situ is most common in women aged 3539 years, while the incidence of cervical cancer is highest in women aged 3034 years (17/100,000). Only 30% of cervical cancers are detected by screening, and the majority of cases occur in women who have never had a smear test or who have not been regular participants in the screening programme. Promiscuity, a sexual partner with promiscuous sexual behaviour and early age at first sexual intercourse have all been associated with a high risk of cervical cancer. The early genes are expressed when the virus enters the host cell and encodes those proteins that regulate viral replication and the interaction with the host cell. Cofactors Cigarette smoking Cigarette smoking has been linked with a higher risk of cervical cancer and has been demonstrated to be an independent risk factor (Winkelstein 1990, Kapeu et al 2009). A recent meta-analysis confirmed that smoking is an independent risk factor for squamous cell cervical cancer, but failed to demonstrate the same for adenocarcinoma (Berrington de González et al 2004). Immunity has been demonstrated for at least 5 years and long-term follow-up studies are ongoing. Natural History and Spreading Pattern of Cervical Cancer Cervical cancers can arise from the ectocervix or endocervix. Most ectocervical cancers are squamous in histology, and endocervical cancers arise from squamous and columnar epithelium. All cervical cancers are preceded by a preneoplastic stage (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia). Cervical cancers may present as an exophytic growth or an endophytic expansion without any visible tumour on the surface of the cervix. The cancer can spread directly to the parametria, vagina, corpus, bladder and rectum. Primary sites of lymphatic spread are the external and internal iliac and obturator lymph nodes, while secondary sites are the presacral, common iliac and para-aortic lymph nodes. Immunodeficiency It has been observed that patients with immunodeficiency disorders, those on immunosuppressive therapy and those 39 Cancer of the uterine cervix Clinical Presentation Patients with cervical cancer may be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Symptoms associated with cervical cancer are often non-specific, such as postcoital bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding, postmenopausal bleeding, excessive foul-smelling vaginal discharge and pelvic pain. Patients with locally advanced cancer can present with loin pain secondary to obstructive uropathy; sciatic pain due to compression of pelvic nerves; and fistula formation between the rectum, vagina and bladder. The positive predictive value of postcoital and intermenstrual bleeding for the diagnosis of cervical cancer in younger women is very low (Shapley et al 2006). Only 2% of patients with postcoital bleeding will be diagnosed with cervical cancer (Shapley et al 2006). Asymptomatic patients are usually referred with either abnormal appearance of the cervix, a suspicious smear or an incidental discovery of cervical cancer on loop biopsy performed for treatment of intraepithelial neoplasia.

This perception of change can lead to a distortion of body image; the woman may sense that something in herself or in her way of relating to others has changed medicine in balance purchase primaquine 7.5 mg without prescription, even before cancer or treatment have any physical effect. It is therefore widely accepted that body image, sexual health and overall quality of life are affected by physical factors, physical sensations, and emotional and social reactions. The specialist multidisciplinary gynaecological oncology support team has an important role in patient education and management of side-effects, aimed at maintaining or improving quality of life. Faced with multiple adjustment demands relating to the cancer, the treatments, survivorship issues or palliation of disease and its symptoms, it is important that the couple are encouraged to prioritize what is important to them and have ownership over agreed interventions. It is essential that this assessment not only covers the cancer diagnosis and treatment, but takes into account what life was like for the woman and her partner/family before the cancer (Box 48. Roles, identity and relationships such as being a wife/partner, lover, mother, daughter, sister, employee or employer, friend and carer may be challenged, threatened and even altered either temporarily or permanently. Issues such as housing, transport, finances, insurance and ongoing responsibilities for paying the bills and child care, along with the challenge of a cancer diagnosis and treatment, may affect her ability to cope. Her usual resources and coping mechanisms and strategies may be challenged to the limit and all this will impact on her quality of life. A needs assessment among cancer patients and their partners showed that 63% of the participants would have liked to receive more information about sexual functioning after treatment, and that 64% would participate in a specific counselling programme on the quality-of-life changes if this was offered (Bullard et al 1980). Model (1990) examined reactions to body image change following surgery in some depth, and linked these to concepts of grief and loss. This is useful as it considers how nurses support both patients and their partners psychologically. Model suggests that we are far from doing this successfully, and that it is important to create an atmosphere in which patients and their partners feel accepted and understood if they experience anxiety, anger or grief, and to provide a medium through which they can express, share and clarify their feelings. Model recommends that the whole healthcare team should work together to do this, which does indeed seem vital, given that many patients and their partners express feelings of isolation following discharge from treatment and for some time thereafter (Colyer 1996). A high proportion of women are anxious (31%) and depressed (41%) after surgery for gynaecological cancer 752 Assessing the needs the effects of both the cancer and treatments have the potential to be both abrupt and long lasting, even when the goal is cure. The impact of altered body image resulting from treatments and/or surgical procedures for chronic illness extends beyond the immediate patient (Wilson and Williams 1988). Therefore, the need for individualized assessment on how this will impact on quality of life, both before and following cancer treatment, is fundamental (Box 48. The changing focus of need Typically, the focus both before and following cancer treatment is on physical need. However, issues such as being unable to continue to work and the consequent reduced income or transport issues due to reduced mobility Qualityoflife Box 48. In the initial stages of diagnosis and treatment for a gynaecological cancer, quality-of-life issues may not seem so important and the focus of concern may be on the tremendous physiological demands that occur as a result of coping with the disease process and treatments. However, as the illness trajectory lengthens, previously held notions may change as a woman adjusts to a new identity as a person with cancer. Quality-of-life assessment and issues relating to the impact of actual or potential change require reassessment during treatment, at follow-up and as part of the long-term rehabilitation process. In women where the cancer progresses or recurs, the goals may change from cure to prolongation of life with the best possible quality for the woman and her family. Criteria for futility must be established to guide the transition from active to palliative management. Rehabilitation and palliation both begin at diagnosis and continue throughout treatment and follow-up. They address the specific desires of each person and it is recommended that they incorporate the contribution of every member of the multidisciplinary healthcare team. In order to achieve this, it is important to identify information needs and individual coping strategies, explore issues identified as important to the patients themselves, and set realistic and achievable goals. Whilst families are often the primary source of ongoing support to female cancer patients, women also derive considerable support from other patients and from healthcare professionals. The medical team should aim to develop psychological and psychosexual skills to cope with this important area of care. What we must learn the following are essential in empowering both nurses and doctors to undertake their role: a comprehensive understanding of the aetiology of the gynaecological cancer and the effects of both the disease and treatment; knowledge of the ways of minimizing adverse problems; and assisting the woman and her partner in managing their needs. Healthcare professionals must develop an appreciation of the wider issues and literature surrounding sexual health, altered body image, gender identity, role identity, cultural 753 48 Supportive care for gynaecological cancer patients: psychological and emotional aspects issues, religious beliefs, and how all the factors can influence self-esteem and body image and impact on quality of life in either a positive or negative way (Masters et al 1995). Concern is often expressed in clinical practice that healthcare professionals lack the time and skills to deal with psychological and quality-of-life issues, although the literature suggests that giving patients the opportunity to express such concerns can be preventive of problems as well as therapeutic (Auchinloss 1989). Despite its importance, quality of life is rarely a reported outcome in randomized clinical trials in cancer patients. Gynaecological oncology nurses, clinicians, educators and researchers must continue to work collaboratively to enhance the knowledge base regarding quality-of-life issues and to improve care provided to women with gynaecological cancer (King et al 1997). She may have been the central supporting figure in a household of some complexity, and may have provided the economic support, as well as the responsibilities of a mother, a partner, a lover and a homemaker. The very act of returning to any or all of these roles is often a significant milestone in recovery. Apart from the obvious anxieties about her prognosis and family relationships, financial worries and change in role can be an immense source of stress for the patient and partner. The potential for this needs to be assessed prior to treatment and at subsequent follow-up. Often practical help can be offered, such as a letter to the employer or facilitating the intervention of social services, and giving information on benefit entitlements and grants. Macmillan) where patients are unaware of possible financial assistance, and help in dealing with transport problems. A malignancy in this area may be especially disturbing and significantly different in its emotional effects from cancer in other parts of the body. Reactions may vary according to feelings of the individual woman about her genitalia prior to developing a gynaecological cancer. An unsatisfactory relationship prior to a cancer diagnosis may be improved by a couple having to cope and coming closer together.

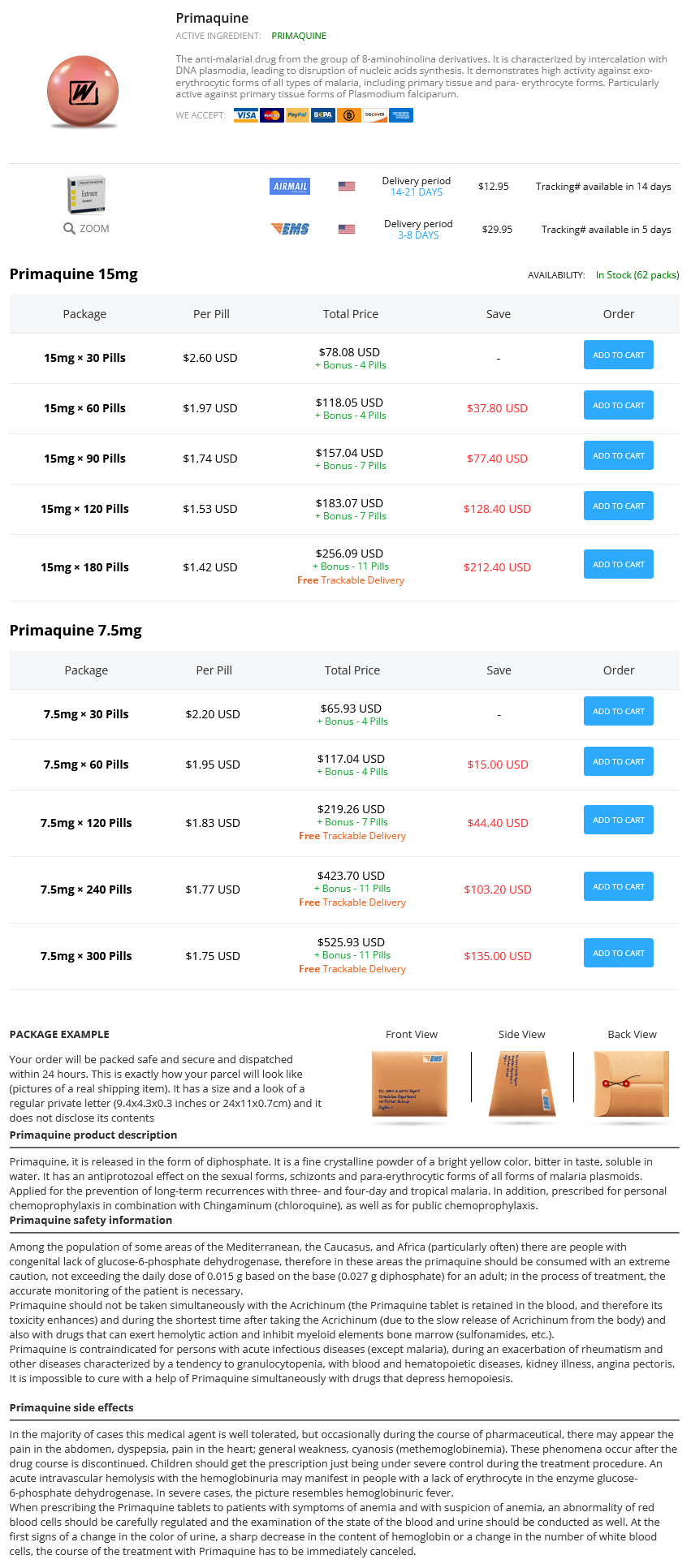

Primaquine Dosage and Price

Primaquine 15mg

- 30 pills - $78.08

- 60 pills - $118.05

- 90 pills - $157.04

- 120 pills - $183.07

- 180 pills - $256.09

Primaquine 7.5mg

- 30 pills - $65.93

- 60 pills - $117.04

- 120 pills - $219.26

- 240 pills - $423.70

- 300 pills - $525.93

The uterus with the fibroid(s) is exteriorized after careful inspection of the pelvis for coexistent pathology treatment of gout purchase 15mg primaquine overnight delivery. The uterine incision is made with either cold knife or cutting diathermy, the fibroid(s) grasped with either a myoma screw or tenaculum, and the fibroid enucleated either with finger or scissors around the usually clear tissue plane of the pseudocapsule. After removal, the cavities left behind should be closed meticulously with figure-8 sutures (the authors usually use absorbable Vicryl sutures) to prevent haematoma collection, and the serosal layer should be closed with a continuous subserosal suture. Complications the two major problems associated with abdominal myomectomy are intraoperative blood loss (which can be severe and may necessitate a hysterectomy to control bleeding in 12% of patients) and postoperative adhesion formation. They are usually a consequence of difficulties with haemostasis and oozing from incision lines. Adhesions after incisions on the posterior wall are potentially more serious because of involvement of the uterine tubes and ovaries. Reproduced with permission of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, formerly the American Fertility Society. Some authorities recommend removal of posterior wall fibroids via the uterine cavity through an incision on the anterior abdominal wall, although this causes a deliberate breach of the uterine cavity and entails a risk of intrauterine adhesions. Keeping tissues moist, using wet packs to displace the bowel and minimal tissue handling is thought to reduce adhesions. The use of barrier agents, such as Interceed, Seprafilm and Gore-Tex, to reduce adhesions has been the subject of a recent Cochrane review (Ahmad et al 2008). While the use of Interceed does reduce postoperative adhesion formation after surgery, there is insufficient evidence to show that the reduced adhesion rates correspond with increased fertility and pregnancy rates. Both mechanical and medical methods have been described to reduce intraoperative blood loss. This also reduced the size of the fibroids by approximately 50%, and reduced pelvic symptoms, operating time, duration of hospital stay, blood loss and rate of requiring a vertical incision. While an increased risk of fibroid recurrence has been reported, due to shrinkage of smaller fibroids making them undetectable at surgery, this was not confirmed in a systematic review. Intraoperative interventions to reduce blood loss during myomectomy have undergone a Cochrane review by Kongnyuy and Wiysonge (2007). It can be used in conjunction with ring forceps to occlude the ovarian blood supply. An alternative is the use of a rubber tourniquet or catheter, placed around the uterus through an incision in the broad ligament at the level of the lower segment. During a long operation, intermittent release of the clamps or tourniquet is recommended every 1020 min to prevent ischaemic damage to the tissues. Those that have been found to be effective (with weighted mean difference in blood loss with their use given in parentheses) include intramyometrial vasopressin (-299 ml), intramyometrial bupivacaine plus epinephrine (-69 ml), pericervical tourniquet (-1870 ml) and vaginal misoprostol (-149 ml). The issue of mode of delivery in subsequent pregnancies following myomectomy where the uterine cavity has been breached is controversial. While common advice given to patients is that all myomectomies involving breach of the uterine cavity mandate caesarean sections in subsequent pregnancies, the evidence for this advice is limited (Parker 2007). During pregnancy and labour, rupture of the uterus after fibroid surgery is an extremely rare event. However, rupture after laparoscopic myomectomy may be higher than after abdominal myomectomy. Resection of the fibroid via the hysteroscope may be combined with endometrial ablation for the relief of menorrhagia if the woman has completed childbearing. Hysteroscopic surgery has been used for the removal of lesions measuring up to 7 cm in diameter, although many authorities would set a maximum of 34 cm (Agdi and Tulandi 2008). Preoperatively, some surgeons use intravaginal misoprostol to soften and dilate the cervix, and allow easier insertion of the instruments. The uterine cavity is distended with a non-conductive glycine solution, and continuous irrigation with an infusion pump is employed to maintain visibility. A loop electrode is placed distal to the myoma, and sliced towards the cervix under vision. The major advantage of hysteroscopic resection is the avoidance of major surgery, as well as easier access to submucosal fibroids compared with the abdominal route. Laparoscopicmyomectomy Despite laparoscopic myomectomy being performed for almost two decades, there is little evidence and considerable debate about its place in the treatment of uterine fibroids. It is still not clear how the complications of the procedure compare with open myomectomy, and reported results from studies and case series are highly operator dependent. The purported advantages of the technique include shorter hospital stay, less postoperative pain, faster recovery and better visualization of adjacent organs (Agdi and Tulandi 2008). However, there have been reports of a higher risk of recurrence of fibroids, due to the inability to palpate the uterus and remove smaller coexisting fibroids laparoscopically. There is also a possible increased risk of uterine rupture in pregnancy and labour. The procedure is challenging, with skills only available at a few centres, and is time consuming compared with an open myomectomy, subjecting the patient to a longer period of anaesthesia. Generally, the procedure involves intramyometrial injection of epinephrine, followed by enucleation of the fibroid via diathermy incision, laparoscopic suturing in multiple layers of the remaining cavity, and morcellation and removal of the fibroid through one of the laparoscopic ports. Treatment methods Recurrentfibroidsaftersurgery Reported cumulative recurrence rates after myomectomy are up to 50% at 5 years, with approximately 20% of women undergoing hysterectomy. From the available literature, a larger preoperative fibroid size, an increased number of fibroid tumours, increasing fibroid penetration into the myometrium and any residual tissue at the completion of the procedure were all associated with increased risk of recurrence.