General Information about Citalopram

The primary use of citalopram is for the remedy of depression. It is FDA-approved for adults over the age of 18, and has been shown to be efficient in managing signs of major depressive dysfunction. It can also be used off-label for other mood problems corresponding to bipolar disorder, anxiousness problems, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. In some instances, citalopram may also be prescribed for premenstrual dysphoric dysfunction (PMDD), a severe type of premenstrual syndrome.

In conclusion, citalopram is a commonly prescribed medicine for the therapy of depression. It is efficient in restoring stability to the levels of serotonin in the brain, which can help manage signs of despair. However, like all medicine, it may be very important focus on any considerations or unwanted side effects with your physician. With correct use and monitoring, citalopram could be a useful device in managing despair and improving general well-being.

It just isn't really helpful to suddenly stop taking citalopram without consulting your doctor first. This can result in withdrawal signs corresponding to dizziness, flu-like signs, and electric shock sensations. Your doctor will work with you to slowly decrease the dosage over time to keep away from these symptoms. It can be necessary to observe the prescribed dosage and not to exceed it, as this will lead to an overdose.

Most people expertise some unwanted effects when taking citalopram, however these are normally gentle and momentary. The commonest side effects embody nausea, dry mouth, dizziness, and drowsiness. Less common unwanted effects may embrace modifications in urge for food, weight, or sexual perform. Some individuals can also expertise agitation, temper swings, or changes in sleep patterns. It is necessary to discuss any unwanted effects along with your physician, as they are in a position to regulate your dosage or switch you to a special medicine.

Citalopram works by inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin, allowing more of the neurotransmitter to stay within the synaptic hole between nerve cells. This results in a rise in the availability of serotonin, which promotes a steady temper and emotional state. By restoring balance to serotonin levels, citalopram helps to cut back feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and anxiousness that are generally related to despair.

Like any treatment, citalopram might interact with different drugs. It is important to inform your physician of another drugs you would possibly be currently taking, together with over-the-counter drugs, dietary supplements, and natural cures. Some medication might work together with citalopram and enhance the chance of serotonin syndrome, a probably life-threatening condition that occurs when serotonin levels turn out to be too excessive. It can be important to keep away from alcohol whereas taking citalopram, as it can improve the chance of side effects.

Citalopram, generally known by its brand name Celexa, is a prescription medicine used for the remedy of depression. It belongs to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) class of drugs, which work by rising the levels of serotonin within the mind. This neurotransmitter is answerable for regulating temper, emotions, and behaviors. Citalopram is available in both tablet and liquid form and is typically taken once a day.

Association between childhood to adolescent attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom trajectories and late adolescent disordered eating medications like zoloft citalopram 40 mg without prescription. Mode of anisotropy reveals global diffusion alterations in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Lewis Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will Know the historical context for the term learning disabilities as well as its definition and implications Be aware of key research findings and the biological basis of specific learning disabilities as well as other impairments associated with learning disabilities Distinguish among intervention strategies, particularly evidencebased practices used in the assessment and identification of learning disabilities Identify the range of outcomes for children and adolescents with learning disabilities Recognize the importance of executive function in the diagnosis and treatment of learning disabilities A great deal of learning involves 1) processing a visual representation of concepts, 2) attaching that perception to language in order to communicate understanding, and 3) demonstrating that understanding with oral or written products. When a child struggles with these subtle and complex perceptual skills, their disabilities in understanding what they are encountering in the classroom impacts their ability to build a "toolbox" for more and more complex learning. This article focuses on those children, who represent more than one third of the students identified with disabilities in the United States (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2017; U. In a 1963 conference organized by parents, Samuel Kirk proposed in his keynote address that the term learning disabilities be used for otherwise normally developing students who struggle with reading, writing, or math acquisition. Following the conference, the parents of students with such learning disabilities partnered with parents of students with developmental disabilities to mount a national political effort to get educational services for the authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Her insights and research perspectives enriched our presentation of the growing body of research and practice in this most challenging area of need. This impairment causes serious difficulties in making daily progress through the general education curriculum at all grade levels. These disorders affect individuals who otherwise demonstrate at least average abilities that are essential for thinking or reasoning. Thus, although intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, seizure disorders, receptive and expressive language disorders, traumatic brain injury, and hearing and vision impairments all can interfere with learning, they are not classified as primary learning disorders. This article describes learning disabilities not as a single disorder, but as a group of profiles that present differently in different children and need to be fully understood in order for intervention to be effective. All of the first-grade teachers in his elementary school provide daily phonological awareness instruction (to help students improve their awareness of phonemes, the sounds that make up syllables and words) for 15 minutes each day during the first 4 months of first grade and daily phonics instruction (teaching students to understand the correspondence between phonemes and written letters and words) for 30 minutes each day during the next 4 months of first grade. During the last 6 weeks of first grade, Noah and his fellow students were individually assessed by the school psychologist on standardized measures of phonological awareness and phonological decoding. This was done by having the students read pseudo words (invented words with plausible English phonology) and then read real words aloud (oral reading). Noah and a number of his peers scored below the 25th percentile on these measures. As such, he was identified as being eligible to receive tier 2 supplementary instruction in second grade in addition to the regular reading program. Upon entering second grade, Noah received tier 2 supplementary instruction in a small group setting that was provided by trained paraprofessionals. This instruction occurred during regular class time when his classmates were engaged in other kinds of teacher-provided instruction in small groups. His classroom teacher reported that he and several other students who had received tier 2 support were struggling with their written assignments, not just with oral reading. As a result, the psychologist included measures of orthographic awareness (the ability to process and use visual representations of letters and words;. She also reached out to the parents of all the students receiving supplementary reading instruction to obtain developmental, medical, family, and educational histories. Careful examination of the profiles for these students identified three patterns of difficulty. For the first group of students, the most prominent problem was with dysgraphia, characterized by 1) impaired legibility and automaticity of letter production, 2) problems with storing and finding ordered letters in long-term memory, and 3) impairments in executive function for planning serial finger movements. Two students with pure dysgraphia profiles were impaired in handwriting rather than reading, but their illegible, slow, nonautomatic letter retrieval and formation interfered with their ability to complete written activities. Thus, a handwriting disability rather than reading disability accounted for their failure to respond to the tier 1 or tier 2 intervention. Noah was in the second group of students, whose main problem was with dyslexia, characterized by 1) impaired word decoding (reading) and encoding (writing and spelling), 2) difficulties with phonological coding of heard and spoken words, and 3) problems with orthographic coding (processing read and written words and retaining them in working memory). These children also had impairments in the integration of phonological and orthographic processing, resulting in both reading and writing deficits. The five students with dyslexia profiles had difficulty translating written pseudo words into oral pseudo words, written real words into oral real words, and spoken words into written words. Two of them (including Noah) also had co-occurring dysgraphia rather than pure dysgraphia. All of these students had difficulty storing and processing written words in their working memory. Their difficulties were characterized by 1) impaired listening and reading comprehension and 2) problems with oral and written expression. He would receive specialized instruction from a special education teacher, and he would also work with an occupational therapist who, together with his teachers, would help him develop improved writing skills. Thought Questions: Why do some students respond to targeted intervention whereas others do not How can schools meet the challenge of providing adequate shared planning time in the school day for true interdisciplinary collaboration The term excludes learning problems that are the result of intellectual disability, emotional disturbance, environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage, or which are a consequence of visual, hearing, or motor disabilities. The definition does not identify the "basic psychological processes" of learning or how marked an "imperfect ability" to learn must be in order to constitute a disability. It is a definition of exclusion; all other causes for the learning problems must be eliminated. Alternatively, the skill that is impaired, such as handwriting in the case of dysgraphia, may be related to processes other than cognitive abilities (Berninger, 2015; Berninger & Richards, 2010; Berninger & Wolf, 2016).

Association between amygdala response to emotional faces and social anxiety in autism spectrum disorders symptoms strep throat 40 mg citalopram fast delivery. The role of radionuclide imaging in epilepsy, Part 1: Sporadic temporal and extratemporal lobe epilepsy. Astrocytes mediate neurovascular signaling to capillary pericytes but not to arterioles. Distinct cerebellar contributions to cognitive-perceptual dynamics during natural viewing. Systematic review of neuroimaging correlates of executive functioning: Converging evidence from different clinical populations. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Seminars in Medical Genetics), 166C, 184197. The use of magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the evaluation of pediatric patients with seizures. Ventriculostomy-associated hemorrhage: A risk assessment by radiographic simulation. Methylphenidate normalizes fronto-striatal underactivation during interference inhibition in medication-naïve boys with attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prefrontal and parietal correlates of cognitive control related to the adult outcome of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosed in childhood. Kang Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will Describe how the neuromuscular and musculoskeletal systems function and are integrated Recognize the common signs and symptoms of neuromuscular and musculoskeletal disorders Learn the utility, appropriate use, and interpretation of standard diagnostic tests for neuromuscular and musculoskeletal disorders Identify the most common neuromuscular and musculoskeletal diseases of childhood and their treatments, including recently developed molecular therapies Together, the neuromuscular and musculoskeletal systems are responsible for the ability to sit, stand, and move; impairments of these systems are major causes of developmental disability in childhood. This article provides a general overview of key anatomical structures, identifies the signs and symptoms of neuromuscular and musculoskeletal disorders, describes common disorders of the neuromuscular and musculoskeletal systems, and reviews evaluation and management methods and principles. Importantly, it explains how an integrated health care and school system can improve the lives of children affected by such disorders. She was born full term after an uncomplicated gestation, but her parents report that she feeds poorly and that milk sometimes pools in her mouth. During the examination, she has a weak cry and has trouble lifting her head from the exam table. Her muscle tone seems diminished when she is picked up, both in vertical and prone positions. Does this infant appear to have a central nervous system or peripheral nervous system disease, and-if so-what features of the clinical presentation would help with the diagnostic evaluation The musculoskeletal system consists of the skeletal muscles, tendons, bones, joints, and ligaments. The electrical impulse triggers the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which jumps across the synapse, or gap, at this junction. Descending corticospinal pathways carry signals from the brain through the spinal cord to motor neurons in the anterior horns of the spinal cord. The motor neurons are generally regarded as being the first segment of the peripheral nervous system. Signals are transmitted from the motor neurons down the peripheral nerves, then across the neuromuscular junction to skeletal muscle. These signals initiate muscle contraction, leading to movement of the musculoskeletal system. Sensory signals are transmitted from the sensory nerves to the spinal cord, and then to the brain, which continuously integrates this information to monitor the state of the environment and the neuromuscular and musculoskeletal systems. Muscles, Bones, and Nerves 141 to receptors in the muscle fiber; and these receptors generate a new electrical signal that propagates through the muscle fiber and stimulates muscle contraction. The sarcomere is the basic contractile unit in the muscle fiber; it is composed of a number of proteins that bind to each other in a dynamic manner. The main function of skeletal muscle is to contract by shortening, thereby moving limbs, with joints used as fulcrums. For example, when you flex your arm at the elbow, the biceps contracts, as does the brachialis; the triceps, however, relax. If all these muscles contracted simultaneously, your arm would be held stiffly in an isometric contraction. Therefore, to move your arm, the brain sends signals that generate contraction of some muscles and relaxation of others in that arm. They range in size from the auditory ossicles (inner ear bones) that measure less than a half inch each at the long axis to the femur (thigh bone), which is roughly 18 inches long in adults. As growth takes place and the bone is subject to different forces, the bone responds by changing its shape, a process referred to as remodeling. These changes usually increase the tensile strength and stability of the bone, making it less susceptible to fracture. Respiratory and Cardiac Issues In most cases, respiratory and cardiac issues do not arise from neuromuscular or musculoskeletal disorders. However, they constitute frequent complications of these disorders, especially respiratory issues. In addition, in rare instances, they may constitute early manifestations of such conditions. Examples include late-onset Pompe disease (a genetic lysosomal storage disorder), in which respiratory distress may be an early symptom, and Becker muscular dystrophy, in which cardiomyopathy is sometimes the first sign of disease. Some neuromuscular disorders affect the respiratory muscles, resulting in an abnormal sleep pattern or sleep apnea (brief periods of respiratory arrest). These children may suffer from daytime somnolence and often appear fatigued or easily distractible at school. It is important to differentiate between tone abnormalities and strength abnormalities. Children can have hypertonia (high tone and an overreactive response to a normal stimulus) or hypotonia (low tone, with a lesser response to a stimulus). Many neuromuscular or musculoskeletal disorders are linked to disturbances in tone.

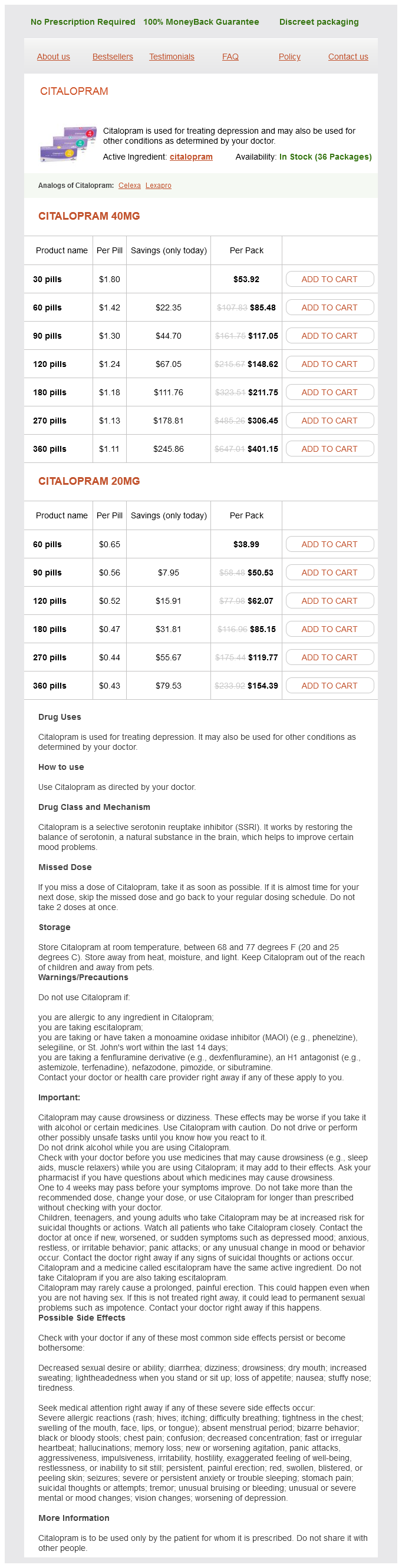

Citalopram Dosage and Price

Citalopram 40mg

- 30 pills - $53.92

- 60 pills - $85.48

- 90 pills - $117.05

- 120 pills - $148.62

- 180 pills - $211.75

- 270 pills - $306.45

- 360 pills - $401.15

Citalopram 20mg

- 60 pills - $38.99

- 90 pills - $50.53

- 120 pills - $62.07

- 180 pills - $85.15

- 270 pills - $119.77

- 360 pills - $154.39

Preverbal communication treatment 0f osteoporosis citalopram 40 mg purchase with mastercard, which is dependent on visual observation and imitation, could be delayed. It is interesting to note that the child with congenital blindness may be unaware of having an impairment until 45 years of age. In the school-age child, however, social skills impairments may be related to social isolation and poor selfimage. Though vision impairment may coexist with dyslexia, there is not a higher rate of vision problems among dyslexic children than the general population (Handler & Fierson, 2017). If vision is thought to be a contributing factor to reading difficulty by a child, their parents, or their educators, they should be referred to an ophthalmologist for evaluation and treatment. Dyslexic children should be treated by an educational therapist specializing in the application of phonics. Dyslexia treatments involving behavioral vision therapy, eye muscle exercises, or colored filters or lenses have not been scientifically proven to be efficacious (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009). Vision impairment is also correlated with high rates of mental health issues, especially anxiety, and the diagnosis of psychopathology and subsequent treatment may differ from patients with normal vision (Saisky, Hasid, Ebert, & Kosov, 2014). With early childhood screening, the risk of persistent amblyopia at 7 years of age is cut in half. Unfortunately, currently less than one in five children receive adequate vision screening. Primary care providers should follow the American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement on eye examination guidelines (American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Ophthalmology, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, & American Association of Certified Orthoptists, 2015). Chapter 7 details these age-specific screening guidelines, which include evaluation for the normal and symmetric red reflex from both eyes spontaneously (the red reflex test), the corneal light reflex or cover test of ocular alignment, and developmentally appropriate visual acuity testing. Any child failing a visual screen should be directed to the care of a pediatric ophthalmologist. Assessing the visual function of children with developmental disabilities is critical in determining the best interventions. It is important to spend time asking the caregivers from their perspective what the child can see or not see, as they observe the child in multiple lighting conditions and in different settings, as well as when the child is rested or tired. Of importance is that their assessment, while not scientific, is more than a one-time snapshot of visual ability. Students who are blind or low vision undergo a formal "functional visual assessment" by a teacher of the visually impaired. In some states, they may also treat medical eye conditions by prescribing eye drops. Some subspecialize to become developmental optometrists or low-vision specialists. They may prescribe glasses; treat amblyopia with patching or atropine drops; treat infections or inflammation with eye drops or systemic medications; and perform ocular and orbital surgeries, including strabismus surgery, cataract surgery, and glaucoma surgery. Getting a child to wear glasses at all can sometimes be a challenge, but most children adapt well after the first 2 weeks of wear. In certain cases, especially in far-sighted patients, an atropine eye drop may be prescribed in order to facilitate glasses acceptance. For children with Down syndrome, Specs4us frames have been specifically developed to better fit their facial structure. For patients with severe photophobia, tinting the lenses can significantly improve visual function and comfort. Contact lenses are less commonly used in childhood due to the difficulty inserting the lens in this population. However, there are certain high refractive error conditions that are best treated with contact lenses because the glasses would be simply too heavy for a child to wear. In aphakic children who have undergone cataract extraction at a young age and lack a lens, they often are prescribed "aphakic" contact lenses of high powers. Contact lenses may also be useful in patients with aniridia, or a congenital lack of a normal iris structure resulting in disabling photophobia. These tinted lenses help block excessive amounts of light from entering the eye, making the child with aniridia more comfortable. There are many children who, due to a medical condition such as autism, do not tolerate wearing glasses at all. There is ongoing research to determine if laser refractive surgery, which is typically reserved for adult patients, is a safe and efficacious way to treat amblyogenic refractive error in this population (Stahl, 2017). Amblyopia Treatment Depending on the cause and degree of amblyopia, treatment may involve glasses, patching, or atropine penalization to blur the vision of the better-seeing eye, encouraging the brain to use and develop the vision of the amblyopic eye (Gunton, 2013). Ophthalmic surgery may be needed in cases of deprivational or strabismus amblyopia. Ophthalmic Surgeries Surgery is sometimes necessary in order to improve vision or prevent further loss of vision. Cataract surgery may sometimes be performed as young as 1 month of age in order for vision to develop properly. Results have shown that amblyopia treatment in general is highly successful, with resolution of amblyopia in approximately 75% of children (younger than 7 years old) when treated with patching or atropine, which were found to be equally equivalent treatment modalities. When either patching or atropine penalization fails to improve vision further, switching to the other treatment modality should be attempted. Surprisingly, almost half of older children (1317 years of age) with previously untreated amblyopia had improvement (10 or more letters) with treatment despite being several years past the classically defined period of visual development (Gunton, 2013). Glaucoma surgery is necessary when the eye pressure is elevated to prevent damage to the optic nerve and subsequent blindness if left untreated. When the eyelid is droopy and covering the pupil ("ptosis"), vision can only develop properly when the eyelid is surgically elevated. This surgery may be done in infancy, like cataract surgery, so that the vision can develop prior to permanent poor vision and nystagmus setting in after 3 months of age. For distance vision, one may use an extra-short-focus monocular telescope, and these may be either handheld or spectacle mounted.